The design decisions and evolution of a method definition - Ruby case study

Episode 01 of studying Ruby programming language design decisions, how they evolved with time, and how they look in a wider context.

This is the first part of what’ll hopefully become a new series and potentially even a book. It is dedicated to studying various elements of Ruby programming language design decisions, how they evolved with time, and how they look in a wider context.

This part is dedicated to method definitions—their general shape and ways to specify arguments. While the topic might seem relatively small, it allows us to take a clearly visible path through a vast design space and see how the language spirit and its initial design decisions shape further evolution.

Also, it might seem weird to choose methods as a starting point to talk about an object-oriented language’s design, but in Ruby’s case, it is fitting. I hope you’ll see why.

Note: In Ruby, all functions are methods, in a sense that they are always belong to some object, even if it is not obvious from the first sight. (We’ll look into this matter in the next part of the series, hopefully.) Nevertheless, most of design questions discussed in this chapter are generic enough to be considered in the scope of languages with no notion of objects whatsoever.

Baseline, and what’s behind the baseline

To see the possible design choices in method definition, let’s start with a very simple one as a baseline:

def log(text)

# some body, maybe just printing to console

endThis is familiar to any user of a mainstream programming language. Save for punctuation, the base is the same in all of them—but even punctuation is usually this in the mainstream: keyword, name, parentheses, argument names, and commas as separators. It is mundane even. It can be said that, despite its reputation as “weird and whimsical” on the foundational syntax level, Ruby follows the principle of being a non-esoteric language.

This common baseline, though, opens many questions and design decisions that every mainstream language needs to do—with an eye to neighbors, competitors and predecessors, but by its own internal logic (or whim of the maintainers).

Some questions to be asked might be: How would you designate optional arguments? How would you declare default values for not provided optional arguments? (And are those concepts related or not? What’s the default value of an optional argument otherwise? Or maybe—like in classic scripting languages—all of the arguments are optional?) How would the types be defined (in statically or gradually typed languages)? What other annotations are possible (like lifetimes, pass-by-value/pass-by-reference, mutability)?

Every answer might have a long-lasting effect on the language’s syntax and semantics—and this list of the questions is by no means exhaustive; note also that those are only questions about argument signatures, not even touching other function/method traits.

How would one approach answering those questions when a young language just starts to take shape?

If the language’s ergonomics is the focus of the designer’s mind, all of the decisions should obviously be considered in the context of how the method calls would look and behave. Would it be pleasant to write and easy to read? Would it require to specify too many unnecessary and obvious details? Would it be suggestive (in writing and reading) for the possible meaning and usage of arguments? Would it be hard to make a mistake, and would reporting on typos and misuses be clear and helpful?

“Classic scripting languages” (like Bash, Perl, or JavaScript) initially tended to prefer succinctness and relaxed treating of input at a price of lesser possibility to spot and understand mistakes. It was an acceptable trade-off when “scripting” languages were used to write, well, “scripts”: short and frequently disposable pieces of glue code.

Ruby can be seen as the offspring of this culture, but its “relaxed” design led to interesting consequences.

A postcard from 🇺🇦

Please stop here for a moment. This is your regular mid-text reminder that I am a living person from Ukraine, with the Russian invasion still ongoing. Please read it.

One news item. On June 12, Russia shelled a residential area of Kryvyi Rih, killing nine people and injuring 29.

One piece of context. A year ago, on June 6, 2023, Russia blew up a large Kakhovka dam, which led to death, destruction, and ecocide. Please read this text about the consequences, a year after.

One fundraiser. Polubotok Treasury has a small, urgent fundraiser for a necessary equipment for several Ukrainian army unit.

On syntax pliability: let’s talk about parentheses

The seemingly small decision of method call syntax might have a deep effect on the overall language’s design.

In Ruby, parentheses in method calls are optional, so log("text") and log "text" are exactly the same—and, in particular, bare name foo is the same as foo()1.

This might seem like a decorative decision (and a questionable one at that), but the actual effect is a compact and pliable language core. Almost every language construct is actually a method call:

class Foo

attr :bar

private

def some_private_method

# ...

end

end

foo = Foo.new

foo.barThis code, which looks very conventional for any mainstream language user, has much fewer atomic language constructs than it might seem because:

attris just a method (of the classClass), a shortcut to create instance methods looking like attributes;so

foo.baris also a method call (Ruby doesn’t have a separate “object attribute” concept, only opaque objects and their methods—which is the opposite of, say, JS/Python’s “object is a dictionary, some of its attributes are callable”);privateis just a method, making all of the methods declared below it private;Foo.newis just a call of the methodnewwhich every class has.

(Not all of the keywords are “actually methods” — class, dev, if, while are core keywords, not following the method calls syntax; again, Ruby prefers being non-esoteric to possible conceptual purity. But, say, math or indexing operators are methods, so a + b is actually a.+(b)—and yes, + is an acceptable method name in Ruby, and you just def +(arguments) in your custom class if you want custom operator implementation.)

Therefore, the syntax built on the decision that “everything is methods and parentheses shouldn’t stay in the way” already makes Ruby feel pliable almost at the level of Lisp: any user-defined method feels native to the language and looks like a deeply integrated syntax. Say, Rails’ well-known “model macros”

class User < ActivRecord::Base

has_many :posts

validates_presence_of :name

# ...…don’t require any additional syntax or rules to be defined: they are just normal methods of the object ActivRecord::Base, called like methods in Ruby are usually called.

Another big “caller side” syntax decision Ruby makes is a concept of “code block” attached to the method, which makes iterators like

array.each { |item| ...or context managers likeFile.open("README.txt") do |file| ...also “just method calls.” But Ruby’s blocks are huge topic, and I plan to cover its design decision and evolution separately.

Argument labels and one more type of brackets

Getting back to “convenience for caller” and how method definitions might be affected by that: many languages sooner or later meet the need to associate arguments on call not by order but by name: foo(param1 = value1, param2 = value2).

There are several reasons such or similar syntax might be desired: to omit some parameters “in the middle” of the parameter list that have reasonable defaults; to avoid memorizing particular parameter order when there are no good unambiguous mnemonics, but parameter names are easy to remember; to make parameter meaning more obvious on the call site (if they meaning is not immediately apparent just from value, especially for boolean ones).

In early versions of Ruby (since as early as Ruby 0.95, which, according to Wikipedia, is the first public release), the quest for labeled parameters was solved by simply allowing to omit one more kind of brackets: {} around the dictionary literal. So, the method call could look like this:

File.open('log.txt', :mode => 'r', :encoding => 'UTF-8')…which was actually just a syntax sugar for

File.open('log.txt', {:mode => 'r', :encoding => 'UTF-8'})and the open method’s signature is just this:

def open(filename, options)(For those not too familiar with Ruby, :mode and :encoding are Ruby’s Symbols: immutable string-like type used to represent internal identifiers. {key => value} is dictionary literal—though for historical reasons, dictionaries are called Hash in Ruby; I am mostly using the industry common name in the text, but “hash” might slip!)

Depending on your taste, one might enjoy the conceptual minimalism of the approach (this was my sentiment back then when I had just learned the language) or be irritated by “things that pretend to look like other things”: a dictionary literal that “just pretends” to be several independent parameters.

Anyway, it worked quite nicely to inspire many APIs and was further improved when Ruby 1.9 (2007) introduced a syntax sugar for dictionary literals with Symbols keys: sym: "value", so the call would now look more succinct, with nothing but names and values:

File.open('log.txt', mode: 'r', encoding: 'UTF-8')Interestingly enough, this was one of the decisions that was met with extremely mixed community response: while definitely nicer to write, it “broke” the conceptual clarity of having any dictionary, regardless of key and value types, written as key => value. To this day, there are Rubyists who prefer to avoid this “sugar.”

But it seems like the sugar’s perception opened the way for further evolution, which I describe below.

Another interesting observation here is that Ruby’s new syntax reminded not only of JS, but also of Smalltalk, where keywords-with-colons is the only way to describe method’s arguments in the signature. In Smalltalk’s syntax (without referring to any particular dialect), the method call above would look this way:

File open: 'log.txt' mode: 'r' encoding: 'UTF-8'…where

open:is both the name of a method and, on call, the name that designates the first argument. Ruby didn’t try to inherit this part of the Smalltalk’s API too hard, though: while many core methods initially have Smalltalk-borrowed names (collect/injectinstead of industry-commonmap/reduce), there is not much core or standard library APIs in early versions that heavily relied on “option dictionaries.”

Of course, Ruby is not the only language that repurposed the key-value collection type for quasi-named arguments (but, to my knowledge, the only one—at least in the mainstream—which made its “sugary” bracket omission a foundation for the perception of this approach). Obvious other example is JS, and, maybe less commonly known, Lua (which documents this in an official Named Arguments chapter of the language book). Some languages, like Zig, use similar solutions with anonymous struct literals

Most of the other (mainstream) languages, though—like Python, C#, Scala—made a choice to leave the decision to the caller site:

# the definition: just the list of args

def open(filename, mode, encoding):

...

# the call: all are correct, any could be named:

open('log.txt', 'r', 'UTF-8')

open('log.txt', 'r', encoding='UTF-8')

open(encoding='UTF-8', mode='r', filename='log.txt')Can’t help myself but put another aside note here, on symmetry (remember this word for later). While some languages (Python, Scala, Kotlin) prefer the assignment sign to bind names to values in method calls (symmetrical to name binding in variable assignment, and default values in method definitions), some, like C# (since version 4.0, released in 2010) and PHP (8.0, in 2020) preferred

name: valuesyntax—probably, in a bow to ubiquitous by then JavaScript.

JS’s and Ruby’s conceptually minimalistic approach was probably a child of its place in the timeline of the dynamic languages. They were, back then, tools for thinking in quick sketches. Such a tool should be expressive yet low-concept, and “sketch/thinking” meant that error handling and robustness were less prioritized.

But, well, times have changed, and dynamic languages have started to be used for writing big systems, perpetuating the argument between those valuing their pliability and freedom of trying things and those who prefer the steel-like reliability of static typing and compilation. (The argument I am absolutely unwilling to participate in. I just observe how one of the languages evolved, with a curious eye on close and distant neighbors.)

So, the demands and challenges changed. Or, rather, stayed the same—quickly and flexibly think in code—just the code now was different.

It is pliable, but it shouldn’t fall apart

It was so easy and convenient as it was in Ruby to make methods with those quasi-named arguments that libraries and application code used it almost inevitably, especially with the ascension of Rails and structured web apps in dynamic languages in general.

The math is simple: reusable, long-living pieces of code with complex structure find themselves in much greater need of large argument lists and clear marking of arguments than one-off scripts and small experimental libraries (previous scripting languages domain).

However the drawback of the conceptual simplicity is that while it helps the method’s callers to express their thoughts freely, it puts a lot of burden on the method’s authors.

Assume (just as an example) that in the File.open method above, mode: is semantically mandatory, and encoding: has a reasonable default of "UTF-8". To implement this fully, the method’s author will need to write something akin to2:

def open(path, options)

raise ArgumentError, "mode is required" unless options.key?(:mode)

mode = options[:mode]

encoding = options[:encoding] || 'UTF-8'

# ...

end(Even those checks aren’t exhaustive: they don’t ensure that options hash have only allowed keys, so it is easy to miss a typo by sending enocding: option, or try to send an option that is not recognized at all.)

Implementing all the necessary checks and defaults properly frequently stalls the thought and feels like an unnecessary ceremony before you can start to write interesting stuff—and consequently, it is always a temptation to “skip it for now,” especially for smaller methods where such checks might take more than the essence of the method body.

Also, with one last dictionary argument for all the options, how would the person using the method know which options are available and which are mandatory? It requires extra effort either from the method’s author (add documentation comments and very clear error messages) or from the method’s consumer (to read through the code).

JS eventually went with introducing destructuring syntax in function definition—and that only in 2015, and only answers part of the challenges:

function open(path, {mode, encoding = 'UTF-8'}) {

// `mode` and `encoding` are available as local variables

}

open('test.txt', {})The call above makes an available set of options visible and sets the default value for encoding variable, but will leave mode as undefined, not complaining it wasn’t provided.

Ruby’s choice in solving the problem was guided by the fact that bracket omission made labeled arguments look real and separate entities—one might say that this big design decision was made possible by syntax sugar!

It was a logical step (and pretty small—if not in implementation complexity, then at least in the programmer’s mental model adjustment) that was made in Ruby 2.0 (February 2013) with the introduction of the “real” keyword arguments:

# if this is how the call looks:

File.open('test.txt', mode: 'r', encoding: 'UTF-8')

# ...then can the definition just use the same syntax?

def open(path, mode: 'r', encoding: 'UTF-8')

# `mode` and `encoding` are available as separate local variables

# in the body

endThere was no semantic trick here; in the method definition, the new syntax was not a sugar for “it is actually just a dictionary,” but a wholly new concept—just looking familiar and consistent with old habits. (Which didn’t save from some community pushback on losing the conceptual minimalism.)

At that first introduction, all “keyword arguments” (that’s how they were named officially in Ruby) should’ve had defaults, so the syntax always looked very similar to key: "value" habit of dictionaries.

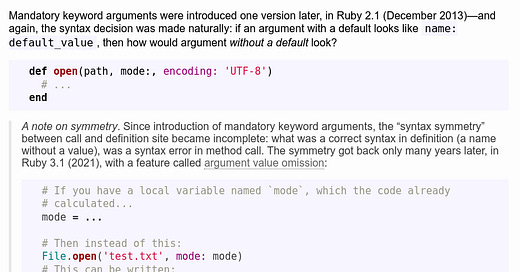

Mandatory keyword arguments were introduced one version later, in Ruby 2.1 (December 2013)—and again, the syntax decision was made naturally: if an argument with a default looks like name: default_value, then how would an argument without a default look?

def open(path, mode:, encoding: 'UTF-8')

# ...

endA note on symmetry. Since introduction of mandatory keyword arguments, the “syntax symmetry” between call and definition site became incomplete: what was a correct syntax in definition (a name without a value), was a syntax error in method call. The symmetry got back only many years later, in Ruby 3.1 (2021), with a feature called argument value omission:

# If you have a local variable named `mode`, which the code already # calculated... mode = ... # Then instead of this: File.open('test.txt', mode: mode) # This can be written: File.open('test.txt', mode:) # meaning the same: use `mode` as a value for a parameter # with the same name(Interestingly enough, there was a huge pushback that time, with the main argument for the new syntax “looking like incomplete code.”)

Overall, this development path—while still staying in the spirit of the language and looking “reasonable” for the uninitiated—has put Ruby in a smaller bin of languages that split positional and named arguments in function definitions. Other languages that made such decisions are, for example:

OCaml — since its v3.0, released in 2000, so one of the oldest and probably the most esoteric syntax for mainstream developers;

much more mainstream-y Swift (2014) — has all arguments named by default and a special syntax to mark some as positional;

…and Dart (2011) uses an interesting syntactical decision to just wrap all the named arguments in brackets without changing the rest of their syntax; some funny antithesis to Ruby’s “just remove brackets” initial design;

Raku, the fascinating offspring of Perl that feels at times like a design lab for new syntax ideas and notably has many syntaxes for calling functions with named arguments, so one can create APIs of many flavors with it.

Evolution is painful: To unpack or not to unpack?

An important concept in dynamic languages—especially those as concerned with metaprogramming and general expressiveness as Ruby—is an ability to accept argument lists with contents known only dynamically and to pass such lists into methods known as “unpacking” of argument lists.

The concept in some form is present in many modern static languages, too, but, as far as I am aware, has much less importance—mainly for special cases like “formatted debug print” (or as a dynamic list of arguments of the same type).

In dynamic languages, though, there are many cases when either the arguments list is gathered dynamically (and then needs to be sent into a method with a defined arguments list), or the method accepts a dynamic, frequently heterogeneous list of arguments to process them uniformly or pass to the next method in some middleware chain; or just drop extra arguments to conform to some generic interface.

In Ruby, like in several other languages, the syntax for “splatting” (unpacking) arguments is implemented via asterisk:

# The most frequent case: accept “whetever necessary”

def logged_open(log_message, *args)

log.info("Opening the file")

# ...and pass the argument into other method, again “whatever it accepts”

File.open(*args)

end

# The syntax is actually pretty flexible, so it can be used in the middle

# of argument list:

def logged_open(path, *other_args, log_message)

# ...

end

# also a _symmetrical_ syntax exists for variable assignment:

first, *rest = list

first, *middle, last = other_list

# The unpacking syntax even allows to handle nested sequences

def foo((left_first, *left_rest), (right_first, *right_rest))

#

end

foo( [1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6] )

# left_first = 1, left_rest = [2, 3]

# right_first = 4, right_rest = [5, 6]

#Keyword arguments required a new kind of unpacking: to gather all named arguments into a dictionary, or, vice versa, to pass the contents of a dictionary as separate named arguments.

A double-splat operator was introduced (probably borrowed from Python) to designate this concept:

# Again: accept any number of _keyword_ arguments...

def wrap_file_open(path, log_message:, **kwargs)

log.info(log_message)

# ...and pass the further

File.open(path, **kwargs)

end

# captures {mode: 'r'} into `kwargs` dictionary, and unpacks it back

# as separate keyword arguments when passing to `File.open`

wrap_file_open('test.txt', log_message: "opening it!", mode: 'r')The new operator, though, wasn’t as symmetrical and powerful as “old” splat. There was no support of the same syntax to unpack parts of the hash into local variables, and no nested unpacking is possible. (This changed with introduction of the pattern matching in Ruby, but it is a separate topic, unrelated—in Ruby—to method definitions.)

At the same time, the code that just accepted a keyword-looking dictionary as a last argument, i.e., the code in pre-keyword arguments style (either old or deliberately written this way), continued to work seamlessly, providing good backward compatibility:

def old_file_open(path, options)

# ...

end

# still implicitly treated as a dictionary last argument

old_file_open('test.txt', mode: 'r')Ruby initially also supported the compatibility between two styles (i.e., auto-unpacking the last hash passed into a method with keyword arguments), which worked “magically” but turned out to be bad magic: a lot of weird edge cases happened when “magical unpacking” happened in an unexpected way (say, mixing default positional arguments with keyword ones, or hashes with symbol and other types of keys frequently led to a confusion). Allowing to mix styles freely also meant that there was less incentive in the community to adopt the new style fully, and there were a lot of codebases where two neighbor files written by two different developers were using different styles (or, neighbor methods in the same class).

Only Ruby 3.0 decisively broke the cursed circle by the so-called “full separation of positional and keyword arguments.” Basically, the auto-unpacking of hashes into keyword arguments (and vice versa, forced repacking of keyword arguments into dictionaries) was dropped.

It was the year 2020, the year of the Tokyo Olympics COVID, seven years and one big version after the introduction of the keyword argument concept. The amount of code that grew during this long co-existence required a long and painful migration process that started in the last version before 3.0 with some deprecations, and some residual edge cases continue to be solved in Ruby 3.1-3.3 (and at least one has been taken care of as recently as an upcoming Ruby version—and the logic of this solution is still questioned).

Both approaches to named argument—the “sugar for a dictionary” and “real” keyword arguments—continue to work, just never to be mixed. There also was a new **nil construct—somewhat clumsy, but a useful way to say the method doesn’t accept keyword arguments and, to avoid confusion, doesn’t allow passing hashes without brackets.

Finally, considering how frequently “pass everything to the next method” is used in Ruby (middleware, delegation to implementations, metaprogrammed wrapper methods), there was a new way to mark “all arguments regardless of their kind”:

def my_open(...)

# some additional code

File.open(...)

end…but only to pass them further: you can’t give such “catch-everything” a name.

Is that all?

We just followed a pretty narrow trail through a design space of a language: a story only concerned with method arguments definition and only to properly support named/labeled arguments and keep the language pliable and convenient.

The path of changes and decisions described was happening over the span of decades and several major versions (and that’s considering that Ruby’s “fractional” versions are frequently a big step in the evolution of the language).

Some sacrifices were made, and some tensions were created in the community, with each new syntax adjustment meeting its share of accusations of “overcomplicating the language for no reason” and “useless sugar.”

For me, the point of this story is not even whether the changes were “good” or “bad” (significant or minuscule, justified or unnecessary). Rather, I am trying to tell a story of how the shape of the possible design space is probed from the point of view of the initial language’s intentions and by the real needs and habits of its users: a story of evolution, both technical and humane.

To wrap it up, I’d like to briefly mention a few side trails—big and small—that were abandoned on the path, still making many people sour.

The most obvious one is a syntax for type declarations. The story of the discussions and possibilities of introducing types in the language is quite complicated; I tried to tell it a year ago in this article; but one part of it is that (besides other reasons) with Ruby’s already rich syntax and omnipresent metaprogramming (in the way that relies on methods pliability), it is extremely hard to come with a way to add types to method definitions so it would look good.

Another topic for dreams and discussions in method definitions is pattern matching. While proper structural pattern matching was introduced in the same time span (around Ruby 3.0) when “the great keyword separation” happened, it stayed a separate kind of statement, and there wasn’t any way invented to merge it with an “old-style” deconstruction, which is less powerful but more deeply integrated into the language—including the deconstruction in the method arguments. I touched this topic a bit by the end of that typing article.

A couple of smaller ideas related to method definitions are discussed from time to time on Ruby’s tracker. One is to allow not only binding to method-local variables but also to instance variables of the object (which in Ruby is marked with @ prefix) by simply allowing def foo(@a, @b) syntax—the idea mostly useful for object constructors and therefore not truly generic— which is maybe why it is constantly rejected.

Another one is to allow binding argument values to local variables whose names are different from the name of the argument:

# So, imagine we have a method that can be called this way:

send_event(on: :monday, if: -> {... some condition ...})

# This method would be defined this way:

def send_event(on:, if: nil)

# inside the method, we need to use `on` local variable:

if Date.today.wday == on # ...which is here not as obvious as in method call

# ...

# And we can’t use `if` variable because it is a keyword, so the only way is

# a verbose:

condition = binding.local_variable_get('if')

# ...

end

# So, what if we could’ve write this (not valid Ruby!)

def send_event(on wday:, if condition:)

# meaning the value of `on:` argument is available in `wday` local variable,

# and the value of `if:` argument is available as `condition`Swift, for example, has such a feature; in Ruby, it was discussed several times (1, 2) but to no conclusion (yet?).

What’s next?

In this text, we’ve covered only a small part of the language design—method arguments definitions. Nevertheless, it helped to establish a methodology for writing about the language elements’ evolution and to define some base language characteristics to expand in future chapters.

Some elements of what can be considered part of the method definition—like visibility, ownership, decoration, redefining existing method—will be covered in the next chapter(s), the nearest one tentatively named “What happens when the method is defined?”

Stay tuned.

Thank you for reading. Please support Ukraine with your donations and lobbying for military and humanitarian help. Here, you’ll find a comprehensive information source and many links to state and private funds accepting donations.

If you don’t have time to process it all, donating to Come Back Alive foundation is always a good choice.

If you’ve found the post (or some of my previous work) useful, I have a Buy Me A Coffee account now—including subscription options with secret posts! Till the end of the war, 100% of payments to it (if any) would be spent on my or my brothers’ necessary equipment or sent to one of the funds above.

When the identifier has an explicit receiver it is applied to (obj.foo), it is definitely a method. If it is just a bare identifier (foo), it might refer to a method or a local variable, whichever is present in the current scope—if both are present, the local variable “wins”. This might sound like something that might induce confusion, but it is actually a useful design tool, which allows to switch from the name of some value being a method to being a current method’s argument to being a locally-calculated variable without changing the code that depends on it. The technique is called “bareword”—a term introduced by a prominent Rubyist and teacher Avdi Grimm.

A note for fellow Rubyists: Of course, Hash#fetch might’ve been used here (both to ensure the presence of a mandatory key and to provide a reasonable default for an optional one), but I am trying to make my examples readable for a wider audience, and using Hash#fetch wouldn’t change the general principle of what I am talking about.