Wikipedia and irregular data: how much can you fetch in one expression?

Using the idea of a phrase-level expressiveness to design a succinct and unobtrusive query language

After months of digging into generative art in JS and handling the recent Ruby version, I am now returning to my Python open data project—WikipediaQL.

It is still in the early/experimental stages, and the last few months of writing gave me the idea that for my mindset, it would be much easier to write about the project and ideas behind it simultaneously with developing.

Previous months of work on WikipediaQL were quite chaotic: I’ve tried to build some feature I imagined should be useful, spent several weeks on it, then it was ready, then I started to write an article… And typically, found out that trying to explain the new idea exposes it lacking some important nuance or being overcooked.

So, this text is written simultaneously with working on a new (minor) version; we’ll see how it goes!

What’s this all about?

I’ve explained the set of ideas behind WikipediaQL in the previous write-up (“Taming the irregular”). In short, I am trying to build “what it says on the tin”: a query language to fetch data from Wikipedia (and then, other MediaWiki-based sites). Like this:

There is, though, one important angle of view on this work I haven’t investigated yet: I am trying to design a way to fetch data in one expressive phrase.

Now that I started to write more texts about my work as an open-source developer, I am trying to build some coherence and openness about what I am interested in. Like, how do you jump from Chinese landscape generation in JS to programming language changelogs to Wikipedia parser, right? The answer is the same that is written on top of my Substack: The range of “my” topics is united by an urge to understand and explain. Or, the problems of knowledge acquiring (with code) and expressing meaning (with code).

There are several challenges I am constantly taking, and that’s what unite my projects and endeavors: I am investigating phrase-level expressiveness, and trying to achieve it in a way that would seem natural (or: intuitive) to the reader and to the writer.

All of the epithets above—expressive, natural, intuitive—could be easily brushed off as purely subjective and therefore impossible to achieve objectively. But I still think there is more to it than “to each their own”/”tastes differ”, and that’s what I am actually working on: uncovering intuitions, expectations, and habits and creating new means of expressions on top of them. Or, more generically: base on existing culture, and try to build new cultural artifacts on top of it.

Designing the “natural” language

As WikipediaQL would hardly be the main language for its user, I wanted to think in terms of a language that you don’t need to learn. Rather, one should be able just can get in one sitting, and then use immediately—maybe with some cheatsheet besides.

So, where do we start?

Looking at multiple example pages (a movie and trying to imagine the extraction of semi-formalized data, we might notice that a lot of semantically meaningful elements can be clearly identified as HTML elements (a list, a link, an image). There is a well-defined and widely used tool/language for information extraction from HTML: CSS selectors. Here would be an important principle 1: start from what is known for your users, without reinventing the wheel: in WikipediaQL, usual CSS selectors like a.foo[href^="https://google.com"]:first-of-type just work.

$ wikipedia_ql -p Mini '.hatnote >> a'

- Mini (marque)

- Mini Hatch

- Mini (disambiguation)

- Cooper-S

- Mini (Mark I)

- Mini Moke

- List of Mini limited editions

- Mini concept cars

- List of Mini-based cars(This prints text of all links in the hatnote see-also paragraphs from the “Mini” page. I’ll explain the logic behind >> below.)

Looking into it further, I identified that some of the elements are easily identifiable for human, but doesn’t have a representation in HTML: “it is in section ‘Discography’”, “it is somewhere in the first sentence”—so I have thrown in selectors like section and sentence.

$ wikipedia_ql --page "Dune (2021 film)" \

'section[heading="Critical response"] >>

sentence:contains("Rotten Tomatoes")'

- On the review aggregator site Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of

82% with an average rating of 7.60/10 based on 420 reviews.Finally, no matter how well-structured the content is, a simple text search is a useful and frequently inevitable escape hatch. So I threw in a pseudo-selector text (and its accompanying text-group): it doesn’t correspond to any particularly identifiable element on the page but allows to select some range of elements.

$ wikipedia_ql --page Raccoon \

'text:matches("raccoons measure between (.+?) and (.+?) cm")'

- raccoons measure between 40 and 70 cm

$ wikipedia_ql --page Raccoon \

'text:matches("raccoons measure between (.+?) and (.+?) cm")

>> { text; text-group[group=1]; text-group[group=2] }'

- raccoons measure between 40 and 70 cm

- '40'

- '70'Principle 2: extend the recognizable base in a predictable way. In early versions, text selector had an unfortunate form text["pattern"]. It was easy to write but hard to explain: it defied every habit about how selectors look in CSS. Since version 0.0.6, due to writing this explanation, it is text:matches("pattern")—corresponding to CSS selector’s distinction of objectively-existing attribute and dynamic function, and removing the unseen in CSS selectors syntax identifier["string"]. This change, by the way, simplified the micro-language parser.

The important thing about selectors of various semantic layers is that they are compatible—so if you see “a link inside that sentence of that section”, you can just say so:

$ wikipedia_ql --page "Kurt Vonnegut" 'section[heading="Novels"] >> li >> { a >> text as "title"; text:matches("\(.+?\)") as "year" }'Note that the sequence of selectors diverges from what’s normal for CSS: I believe that parent child would be too confusing for a query language, making trivial typos in complex queries changing the semantics. I went through several approaches with this: started with parent { child }, then for simplest cases introduced the shortcut parent >> child—it was inspired by XPath’s distinction if parent/immediate_child and parent//any_child; so if in CSS selectors parent > immediate_child is a thing, I believed a stretch to parent >> any_child should not be far from acceptable. While writing this article, I’ve reviewed the system and simplified it to have >> as the only way of nesting, leaving {} only for grouping.

So, let’s call it principle 3: diverge from usual when there is a good reason to, but try to do so in an explainable manner.

The efficient implementation of the multi-layered selector’s system wasn’t an easy task (and at these early stages, internally it is quite ugly don’t look please don’t look why did you look), and I am perfectly fine with it. I am coming from Ruby, which has “complex language to write simple code” as one of its semi-official mottoes, and I can state that my principle 4 is consent that humane/natural API might be complex to implement. As far as this complexity has clearly defined rules and is well-contained, it is acceptable.

That’s about the size of the language. As I’ve said: just a few syntax elements, most of them already familiar, and a dictionary of possible words that can grow with versions. There are also a few parts related to multi-page fetching, but we’ll get to it later.

But, to my mix of excitement and contempt, it is only a start of implementation complexity.

Consent to internal complexity

The visible simplicity of the language doesn’t necessarily imply the simplicity of the implementation. I want the query language to be useful, not just beautiful-for-demos. And this means we can’t avoid parts o the data that should be simple to query, but the underlying structure makes them complex.

There are several parts of your typical Wikipedia page that have a simple mental model but a complex DOM model. Those are typically most formalized—and therefore most useful!—parts.

Take this climate table (I already briefly used it as an example in the previous article):

How would you say “average low in January”? Or “all temperature values for January”? Or “daily mean for all months”? It should be simple, right?

So I started from the mental model: average low in January should be pronounced (preserving all the language elements we made up above) somewhat like tr[title="Average low °C (°F)"] >> td[column="Jan"]. Or maybe even td[row="Average low °C (°F)"][column="Jan"], why not.

And in WikipediaQL, this works:

$ wikipedia_ql -p Kharkiv 'section[heading="Climate"] >> table >> table-data >> td[row="Average low °C (°F)"] >> td >> { @column as "column"; text as "value" }'Note the pseudo-element table-data in the query. That’s where the magic happens— Except that I hate this phrase and tools pretending that something happened magically, without the user of the tool needing to think of it (read: or understanding what’s going on, or understanding where to look if something is broken).

That’s why there is table-data pseudo-element: it is an explicit statement to prepare a DOM structure that would be “natural” to navigate. I am still thinking about this balance between natural and explicit. (One of the problems, say, is that if you use [column=...] selector without applying table-data before, you’ll see no data at all. That probably can be handled on a query pre-processing stage: all in all, no element could have row/column attrs unless they are inside the table-data.)

In its current implementation, table-data table reflowing “selector” does much more than just attaching row/column attribute (if it would be just for that, maybe that could’ve been done by default). Consider this table—that’s how the TV shows episodes are typically rendered:

Note how the full-row-cell with episode synopsis is “logically” just a long cell belonging to the previous row. At the same time, it is completely regular—and defies any generic table parser. But not WikipediaQL, you know :)

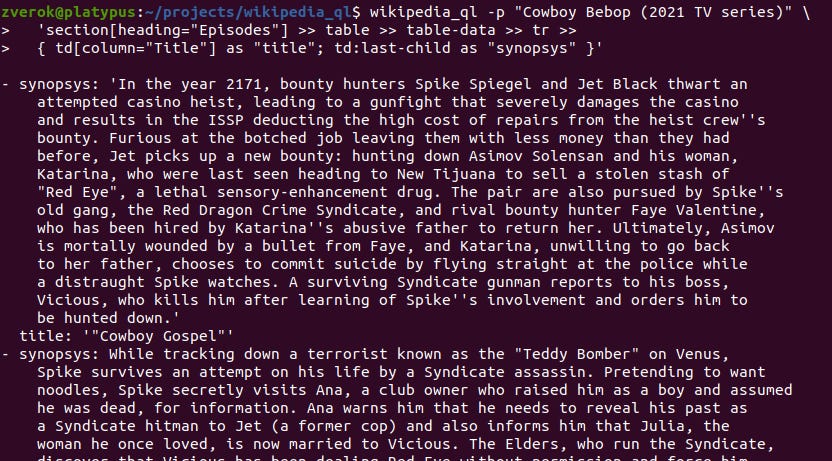

$ wikipedia_ql -p "Cowboy Bebop (2021 TV series)" 'section[heading="Episodes"] >> table >> table-data >> tr >> { td[column="Title"] as "title"; td:last-child as "synopsys" }'table-data catches this known in Wikipedia pattern of using full-row table cell and just attaches it to the previous row instead. Several other things are done in table reflowing: some of them are of generic use (normalizing joined columns and rows), some other Wikipedia-specific, see the full and growing list.

It is complicated. It is irritatingly heuristic and works only for formatting approaches that I deduced to be frequent in Wikipedia. But it is also contained in one module (don’t look there either), and pluggable in a singular selector. I hope it to be a seed of contained extensibility of the query language.

What’s next?

The unticked boxes in my README-aka-TODO are still numerous, but the high-level plan is simple:

Extend dictionary of supported selectors/concepts for some time: we need at the very least infoboxes and hatnotes; most probably, some of the other formalized elements, like navboxes

Make the selectors and their features that emerged work consistently and predictably with each other (for example, currently you can’t say

sentence:firstorli:matches("regexp")—but you definitely should be able to!)Improve handling of multi-page queries: even today, WikipediaQL has

->link-following operator, but there is a lot more to be done with multi-page fetchingStop, look at what I have, polish it, formalize, optimize and document.

One of the end goals here is to have code structured, described, and formalized in a way that will make porting it into other languages easy. I am interested in following the idea of the “query language for Wikipedia”, and if it is worth the attention, also making it followable by others.

Honestly, I don’t want WikipediaQL to be a monstrous “framework” to build through many years. I want it reasonably finished and reasonably useful in the next 4-6 weeks.

Now, I wonder whether this development journey seems to be an interesting read; will several more emails about how it goes be welcome? (Honestly feeling a bit embarrassed to expose my development/thinking process… like some weird kind of OnlyFans, but for OSS development.) So, please don’t hesitate to give honest feedback, if you have any!

Give it a try

Just

$ pip install wikipedia_ql

…and try some of the examples from above, or invent your own?